About MapMob

Who we are

NYU mHealth is an academic research group located within the College of Global Public Health at NYU. Research groups like NYU mHealth exist to help both stakeholders and decision-makers understand the complexities involved and (hopefully) make empirically-based decisions (i.e., decisions based on valid data collected from real-world contexts).

The lab was funded by several bodies. Among those; the National Institute of Health (NIH) National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), NIH National Cancer Institute (NCI), NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research (OBSSR), Truth Initiative Foundation, NYC’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and Washington DC’s Department of Health.

Boundaries Matter

Cities are complex systems consisting of multiple components and resources which coexist in order to provide transportation, food, recreation and workspace for its inhabitants and visitors. Planners, public health, and transportation professionals as well as elected officials are making daily decisions commonly assuming that neighborhood conditions affect the health and wellbeing of those who live and /or work within them.

But wait - which “boundaries” should be used to define these neighborhoods? Which boundaries promote health and well-being in a way that is the most likely to benefit the community? Which are likely to promote social change and equity, and which ones are more likely to deepen community disparities? Which are arbitrary and harmless, simply there for government and other administrative purposes?

Neighborhood boundaries matter, a lot. The problem is that the geographical unit of analysis has a vast influence on the way decisions are made, and one size does not fit all: different analyses often demand different boundary estimates. “Administrative” boundaries are useful for many purposes, but they do NOT tell us all we need to know about the complex network of factors that affect human health and well-being.

At the heart of the matter is the need for scientifically “operationalized” definitions of neighborhood boundaries that are “valid” in the sense that they capture what some scientists call each neighborhood’s true spatial extent.

MapMob is a user-driven project that generates dynamic neighborhood boundaries through crowdsourcing, reflecting both the built and socio-cultural characteristics of the places and people they encompass.

MapMob: Crowdsourced Boundaries

MapMob is a participatory or “citizen-science” project that generates dynamic neighborhood boundaries reflecting both the built and the socio-cultural characteristics of the places and people they encompass.

The foundational premise of the MapMob project is that neighborhoods are “emergent” phenomena that arise from the everyday activities of residents. Put another way: assuming neighborhoods are the product of their individual parts, MapMob aggregates data on the parts to better understand the whole.

What makes MapMob different is that it does not rely exclusively on fixed household address locations to calculate neighborhood or other demographic estimates. Instead, MapMob captures the interaction between home addresses (i.e., residents’ daily starting point), and individual-level activity spaces (i.e., the places residents travel and spend time). As a result, MapMob accounts for the way residents use all of the neighborhoods they visit, not just their own, and thus the way neighborhoods (in the latent sense) exchange people, goods, and services each day.

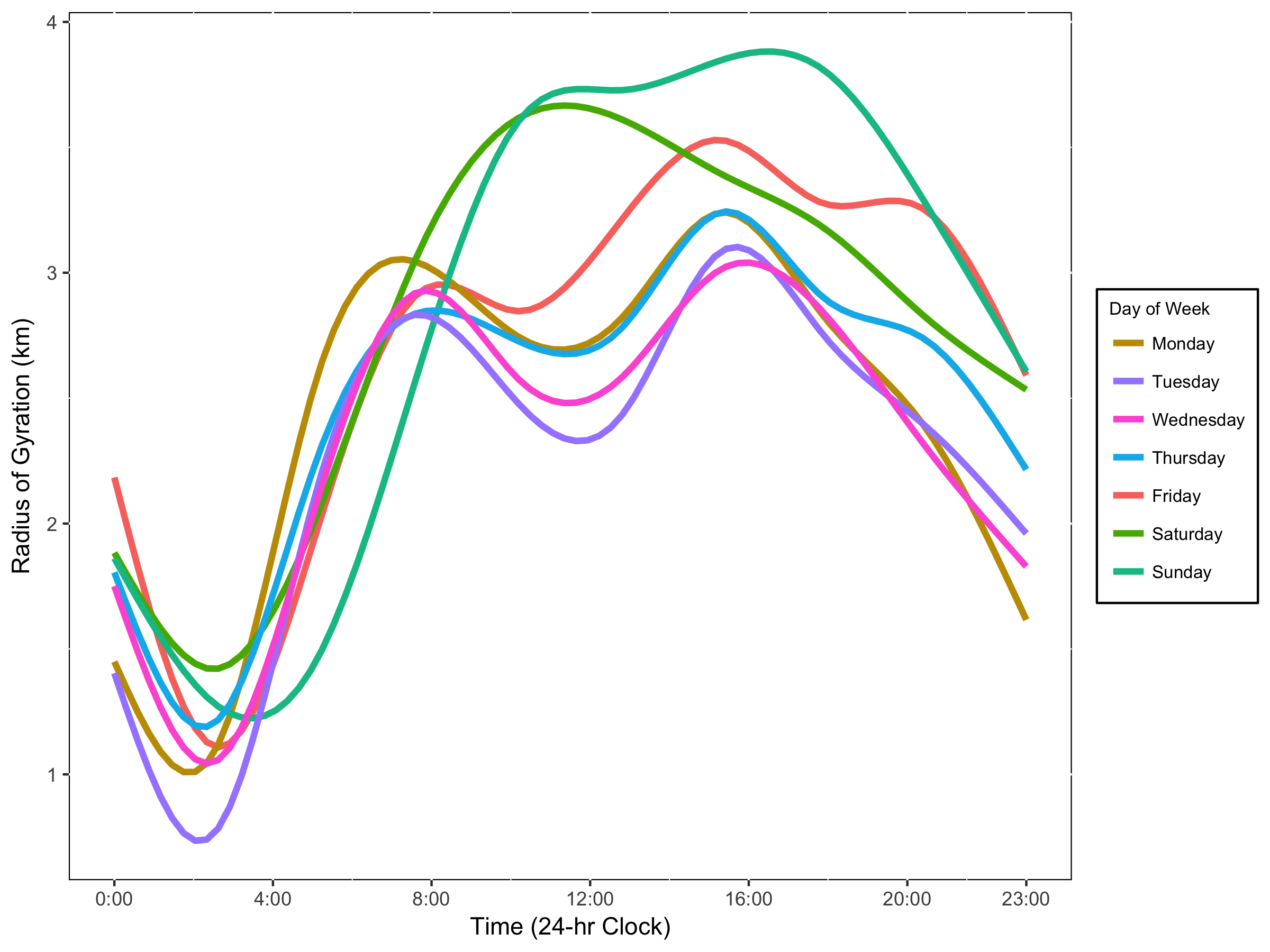

In our research paper, Individual Mobility and Uncertain Geographic Context: Real-time Versus Neighborhood Approximated Exposure to Retail Tobacco Outlets Across the US, we demonstrated the use of geolocation data to capture people's (N = 363) mobility patterns (see also Figure 1). The distance traveled hourly is approximated by the radius of gyration (Rg), where larger values indicate more mobile. Within each day of the week, Rg was the lowest in the middle of the night and higher across the remainder of the day. Two spikes were observed in Rg during early mornings and late afternoons on weekdays, which is likely related to people commuting between home and work (and vice-versa). Additionally, the figure illustrates the divergence on Saturdays and Sundays, when early Sunday afternoons are revealed as the window for greatest mobility on average.

Figure 1 Mobility Patterns by Time of Day and Days of Week.

Administrative Boundaries

What we call “administrative” boundaries are those that are used by government agencies to assign political representatives, oversee zoning ordinances, assess neighborhood conditions, and allocate municipal resources. US Census “tracts” or “block groups,” for example, are defined by polygon-shaped borders that are used to classify households and describe the socio-demographic characteristics of residents. Census estimates are commonly aggregated into larger, aggregated areas, such as NYC “Community Districts,” or “Neighborhood Tabulation Areas”.

Administrative boundaries are an essential tool, but if misapplied they can produce misleading and sometimes politically controversial results. When they are defined by [or derived from] administrative boundaries, neighborhoods are operationalized as collections of residential households that are located in close geographic proximity to one another, in the Euclidean sense. As a consequence, residents within these boundaries begin and end most of their days in the same general area, a basic fact that anchors the time and effort they must expend to access resources each day. Such daily inter- and intra-city migration dynamics are not captured by standard administrative boundaries like those derived from the Census. When taking into account only administrative boundaries, those who commute or regularly visit neighborhoods other than their own are not counted, which is why standard address-based neighborhood estimates cannot account for the non-home activities of residents. Because traditional probability-based surveillance methods also rely on household address-based units to construct their sampling frame, they are limited for many of the same reasons administrative boundaries are limited.